Deep Dive on Ducted Heat Pumps

Air source heat pumps powered by electricity (from here on out referred to as heat pumps) and used in conjunction with propane furnaces or as standalone units have significant operational and carbon savings benefits compared to only using propane. Compared to electric resistance heating, air source heat pumps are significantly cheaper to run. And compared to natural gas, heat pumps have comparable operating costs but significant carbon savings benefits.

Heat pumps come in two forms–ductless or ducted–and there are many configurations of each. We’ll cover ductless heat pumps in a future newsletter. This explainer is about the second type, ducted, which has the primary benefit of being able to be integrated into the existing ductwork of our homes. In this explainer we’ll cover the ins and outs of ducted heat pumps by looking at how these systems are configured, where they work best, and their overall suitability for our climate.

The Basics

To start, ducted heat pumps can be used in a few configurations. Some make sense for certain situations while others don’t, so here’s the basic rundown of the possibilities.

The first type is a dual fuel heat pump. In this configuration, the heat pump is paired with a gas furnace, just like a conventional central air conditioner is. There’s an outdoor unit, called a condenser, and an indoor evaporator coil that sits between the furnace and the ductwork. Like an air conditioner, the heat pump can provide cooling. Further along in this explainer we’ll get to why this type of system might make sense for you—chief amongst them being lower operational cost compared to a conventional gas furnace—as well as some of the limitations.

The second configuration is a ducted heat pump without the backup gas furnace. In this case, both the furnace, outdoor air conditioner condensing unit, and air conditioner coil (which sits above the furnace) are replaced with a new outdoor heat pump condenser and an indoor air handling unit. An air handling unit does everything a furnace and AC coil do, except it isn’t powered by gas; it is powered by electricity. This type of setup is perfect for new construction where heating and cooling loads tend to be low (since new construction is being built to modern energy conservation codes and specs). Backup resistance heating can also be incorporated into the air handling unit to provide supplementary heat when the heat pump isn’t able to meet heating needs.

The third category is low and mid static pressure air handlers. These units are unlike the previous configurations and serve individual zones of a house–like one for each level of a house–or to provide heating and cooling to specific rooms. The units can be mounted on the ceilings of closets or utility rooms or in basements, and have short duct runs that serve limited numbers of rooms. Low and mid static units are an entirely different conversation, and we’ll include them in a future explainer about ductless heat pumps

Left: Dual fuel heat pump with outdoor condenser, indoor gas furnace and heat pump evaporator coil. Right: Dedicated ducted heat pump with indoor air handler and outdoor condenser

But before we get into the nuts and bolts of these two heat pump configurations, it might be best to step back and look at some of the operational cost realities, challenges, opportunities and general misconceptions of using heat pumps in our climate.

Some of the Misconceptions

If you follow energy-related news, you’ve likely heard electrification evangelists say heat pumps are incredibly “efficient”. I recently read an article that said heat pumps are 4.5 times as efficient as gas furnaces, and that running one could save you $1,000 annually. Yes, heat pumps are “efficient”, but no, relative to the price of natural gas, they cost the same if not more to operate in our climate. However, compared to the price of liquid propane—which our rural neighbors use to heat their homes—the price of running an efficient air source heat pump is about 1/3 less expensive. Thus, there are real cost savings for rural customers, but that’s only if you’re in need of immediate furnace and AC replacement. Given the relatively modest savings associated with switching from propane to an electric heat pump, replacing a good furnace and AC doesn’t make financial sense unless the existing equipment is near the end of its operational life. But if your motivation is first and foremost to kick the fossil habit, and your electricity source is relatively renewable, then go ahead.

And as fossil markets become increasingly shaky and subject to weather events, war, climate change, etc, there is really no hard-and-fast rule that natural gas and propane prices will remain low. As the last year has shown, fossil fuel markets are subject to huge price volatility. If the cost of operating a heat pump is on par with natural gas, why bother at all? We know fossil fuels drive climate change, and there’s no escaping the reality that burning natural gas or propane to heat our homes contributes to the problem. We also know that over time the electricity sector—unlike many other sectors of our economy—has rapidly decarbonized. For example, last year MiEnergy—the REC that serves a large portion of Winneshiek County—had a power mix that was 39% renewable, and this year they’re on track to achieve 42%.

Generally speaking, heating loads for new residential construction (per area of living space) are considerably less than older construction. Materials, building codes, construction methods, and an eye toward efficiency have all contributed to new housing being more efficient. In these cases, heating with just an air source heat pump makes sense, especially if the house doesn’t have access to natural gas. And being able to design and take advantage of suitable solar, as well as bundling solar into the initial home construction financing, sweetens the deal further.

Cost of Operation

Climate issues aside, the cost of operating a dual fuel heat pump can be significantly lower than just using propane. For natural gas customers, the cost of running a gas furnace with a heat pump will be about as expensive as just using gas, but the carbon savings can be significant (and depend on how your electricity is produced).

The efficiency of an air source heat pump varies with the outdoor temperature. The colder the outside air, the harder it is to extract heat, resulting in decreased efficiency and output. By using a dual fuel setup, where the heat pump operates when it is cost advantageous to do so (for example, and depending on the efficiency of your heat pump, when it’s about 20-25 degrees and warmer), and the gas furnace for everything below that point, there’s cost savings to be had.

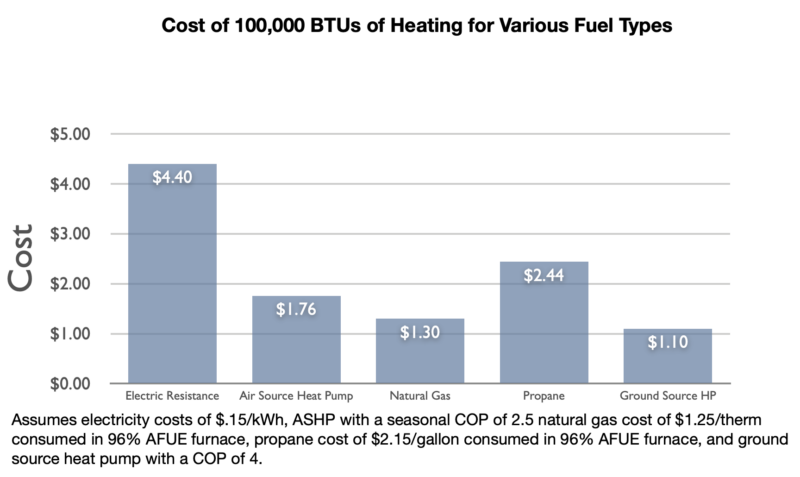

Below is a cost comparison of different fuel types I ran a few weeks back, and if there’s one thing to note it’s that costs for natural gas and propane are up significantly year over year, while the price of electricity remains about constant. The numbers themselves don’t necessarily provide context, but the height of the bars do. Geothermal (ground source heat pumps) are the clear winner in terms of operational costs, but since the complexity and cost of entry into such systems is so great, it’s not a realistic alternative for many of us.

The Need for Backup Heating

Air source heat pumps have come a long way in the past decade. New models are capable of achieving near full output at extremely cold temperatures with decent efficiency. Nevertheless, in our climate, you’ll still need some source of backup heat, whether that’s a gas furnace, resistive heating incorporated into the heat pump air handler, baseboard or wall heaters, a wood stove, or something else entirely. And keep in mind you may already have an installed backup heating system, like a gas or propane furnace to pair with the heat pump, wood stove or baseboard electric.

When I transitioned my house from natural gas to ductless heat pumps three years ago, we retained the furnace and use it only on the coldest days (we still use gas for our water heating and cooking). When we installed the heat pump we also built a new two story addition. To achieve backup heat in that portion of the house, I installed two electric wall heaters, but have never turned them on in three years of using the heat pump.

Perhaps contractors and homeowners dwell too much on the fact that some sort of backup heat is required, which probably explains the psychological stumbling block of some who are hesitant to push heat pumps. Backup heat, after all, is essentially a secondary heating system. Yet given the fact heat pumps have come such a long way in terms of output at cold temperatures—and that in our climate you can easily design a system to provide full heating without backup for over 99% of the hours within an average year (or for all but about 88 hours)—the issue of backup heat is perhaps a bit overblown.

The reality is that contractors don’t prefer one heating fuel over another. Contractors are, however, motivated by market conditions and aren’t necessarily interested in forging into new territory on their own, especially if there are perceived equipment performance-related limitations. So, the more of us that ask questions and express interest in electric-only HVAC solutions, the quicker contractors will come along.

Dual Fuel Ducted Heat Pumps

The simplest (and likely cheapest) point of entry into the electrified world of space heating is to swap your existing air conditioner and coil with a new heat pump. In this scenario, the heat pump will provide heating to a specified outdoor temperature, at which point the gas furnace kicks in. Operationally speaking, utilizing a dual fuel setup can be cheaper than just using natural gas or propane. In the current cost environment—and depending on the efficiency of your equipment—the outdoor temperature at which it becomes more advantageous to run a heat pump than a natural gas furnace is about 20-25 degrees Fahrenheit and higher. Below that temperature, the gas furnace is cheaper to run. For propane customers, the cost at which it is cheaper to run a heat pump than a furnace is about 5 degrees Fahrenheit.

The market for dual fuel solutions has grown by leaps and bounds over the past few years, and there are many products that have good outputs down to about 15 degrees with decent-ish efficiencies as compared to, say, ductless equipment. If you choose the dual-fuel path, definitely go with an inverter-driven (direct current) outdoor condenser as opposed to the traditional single and dual stage (alternating current) condensers commonly used in the southern portions of the US. The outputs of single and dual stage condensers drop off a cliff at about 30 degrees and are basically worthless in our climate, whereas newer inverter driven machines are designed to operate in colder climates. If you inquire about a dual fuel heat pump to replace your existing AC, make sure your contractor understands what they’re installing. A conventional single or two stage heat pump will not produce meaningful savings and will perform poorly below about 35 degrees.

If you’re interested in why single and two stage air conditioners and heat pumps installed in the United States are generally really poor performers, check out this content sponsored article (ad) on Canary.

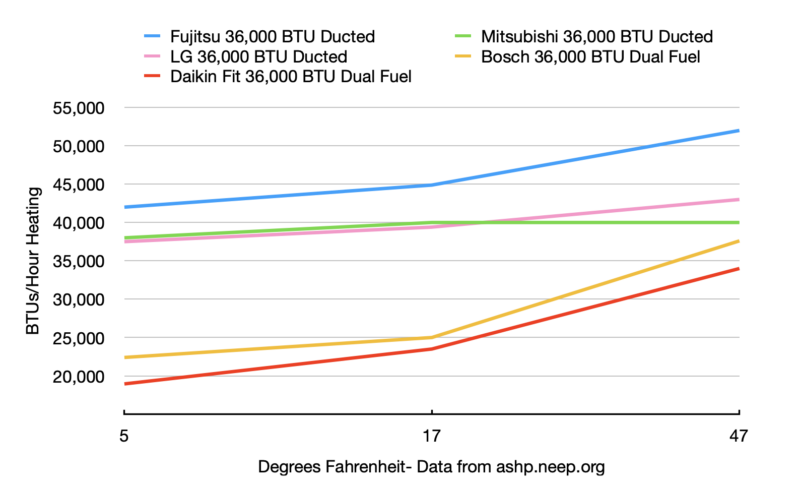

If your motivation is to transition away from fossil fuel use entirely, dual fuel setups probably aren’t the solution, or at least not so in this climate. Yes, you can reduce your operational costs and gas consumption, but you’re still going to use a heck of a lot of gas. Below is a graph I put together that compares BTU output of 36,000 BTU-rated inverter driven dual fuel heat pumps from Bosch and Daikin (marketed as colder climate capable solutions) along with heat pump-only 36,000 BTU models from Fujitsu, Mitsubishi and LG. You’ll notice outputs drop off a cliff at about 15 degrees, at which point you’ll be forced to rely on your gas furnace. So if your goal is to significantly reduce or eliminate gas consumption, a dual fuel setup will get you only part of the way there.

The market for dual fuel setups continues to grow. If you’re inclined to learn more, I suggest you start by looking at Bosch’s dual fuel equipment or the Daikin Fit. One offering I’m super excited about is the Mitsubishi Intelli-Heat dual fuel coil that can be hooked up to its own outdoor mini split-style condenser or used as part of a multi zone setup. For those of us who live in older two story homes with poorly designed and constructed ductwork, you know how difficult it can be to achieve decent cooling on the second floor. With Mitsubishi’s new offering, being able to tie a duel-fuel coil with a second floor ductless wall unit for air conditioning is a game changer. Other manufacturers are surely working to come up with similar offerings.

There are a number of challenges associated with dual fuel setups and ducted heat pump retrofits in general. First off, in an old house ductwork can be pretty rudimentary and inefficient. In my house, the uninsulated, unsealed ductwork snakes through the cold, unfinished basement. Heat rises, and with a gas furnace blasting out 135 degree hot air, the penalty for this design flaw is perhaps not that noticeable. But with an air source heat pump, conditioned air drops with the outdoor temperature. When it’s 40 degrees outside, the heat pump is pushing out 130 degree air, but when it’s -15 degrees, the heat pump is pushing air that’s only 90-95 degrees. As a result, the volume of air required to achieve the same amount of BTUs of heating is potentially much more than what the ductwork can support, resulting in annoyingly loud operation, reduced efficiency, and premature equipment failure.

Another potential limitation with a dual fuel setup is that you’re relying on the furnace blower motor to push air through the ductwork. If your furnace is relatively new it probably has a highly efficient variable speed blower motor, but if your furnace was bottom-barrel quality or on the older side, it likely has an inefficient blower motor, which will significantly reduce overall system efficiency. If you have a relatively new furnace but the AC failed or is near the end of its life, a dual fuel setup might work well for you. But if both your AC and furnace are on the older side, it’s likely advantageous to replace both, or instead, opt for a ducted heat pump without a gas furnace.

Ducted Heat Pump Without a Gas Furnace

In this setup, the furnace, air conditioner coil, and outdoor air conditioner are replaced with a new outdoor heat pump and an indoor air handler. The air handler has coils inside it that provide both the heating and cooling, as well as a blower motor, and it’s all integrated into the existing ductwork. All the major manufacturers, like Mitsubishi, Fujitsu and LG have options with excellent output and good efficiencies, even at the coldest of cold temperatures.

And unlike top of the line inverter driven dual fuel options where output and efficiency drop off a cliff at around 15 degrees, dedicated heat pumps have good outputs down to as low as -20 degrees (at about 75%-90% of their rated nameplate heating capacity). And in those situations when the heat pump can’t meet the heating load of the building, the unit automatically supplements with electric resistance. The operational efficiency of these models at -15 degrees Fahrenheit is around 1.75 – 2x as good as electric resistance heating.

In Conclusion

Having lived in a big, old, drafty house served by forced air heating and cooling, I can say with some authority I’m not much of a fan. Blasting air through the house in the dead of winter feels cold, even if that air is warm. And given the fact the ductwork in old houses tends to be inefficient and leaves certain areas too hot or cold, it seems unwise to tout systems that don’t work well. But the reality is that most houses have ducted systems—and in many cases they function ok—and for those situations a ducted heat pump just might be the easiest entry into electrified heating.

Beginning January 1, the new federal heat pump tax credit comes into effect. The credit is valued at 30% up to $2,000 for heat pumps used for both space and water heating. The credit can be used annually, meaning you’ll be able to prioritize and focus on certain aspects as time and budget allow. In addition to the tax credit, a new rebate program will come into effect that will pay up to 100% up to $8,000 for heat pump installations for those making below certain income levels. Check out our fact sheets to learn more about the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits and rebate programs.

If you’re interested in transitioning your home to heat pumps, give me a call or please email me. For a reasonable fee I can come out and analyze your situation and help you come up with a plan. Heat pumps work well in our climate, are a viable way to lessen your home’s environmental impact and in many cases are cheaper to operate.